Ataxia

Definitions :

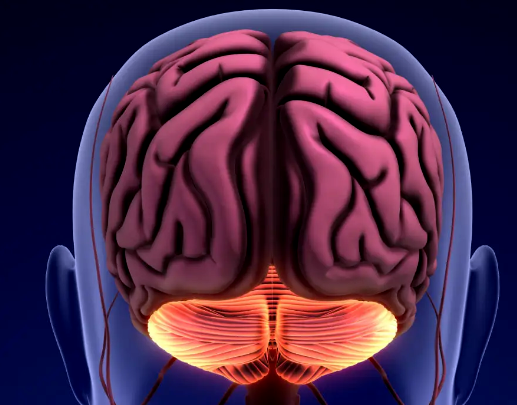

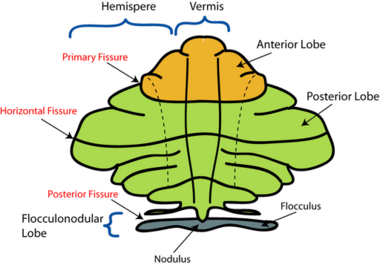

The cerebellum lies in the posterior fossa and consists of two hemispheres with a central vermis. In general, midline structures, such as the vermis ,influence body equilibrium, while each hemisphere controls ipsilateral coordination.

Lesion of the cerebellum lead to :

Ataxia: is a lack of voluntary coordination of muscle movements, which can affect gait, posture, and fine motor skills. It results from a dysfunction in the cerebellum or its connections( Afferent and efferent pathways convey information to and from the cerebral motor cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, vestibular and other brainstem nuclei, and the spinal cord), leading to impaired balance and coordination.

Anatomy and Function of the Cerebellum

- Flocculonodular Lobe:

- Inputs: Receives sensory information from the vestibular system (balance and head position).

- Outputs: Sends signals to oculomotor nuclei to help coordinate eye movements and maintain gaze stability.

- Cerebellar Vermis:

- Inputs: Receives proprioceptive input from the body (muscle and joint position) and vestibular information.

- Outputs: Modulates output to axial muscles for posture and balance, influencing eye movements.

- Cerebellar Hemispheres:

- Inputs: Receives sensory information from the limbs (proprioception) and motor planning areas of the brain.

- Outputs: Sends signals to motor cortex and brainstem nuclei to fine-tune voluntary limb movements and assist in coordinating eye movements indirectly.

Clinical features :

Cerebellar Hemisphere Ataxia:

- **Dysmetria**: Inability to control the range of movement, leading to overshooting or undershooting targets.

-**Dysdiadochokinesia**: Difficulty performing rapid alternating movements (e.g., pronation-supination).

- **Intention Tremor**: Tremor that occurs during purposeful movement, worsening as the target is approached.

- **Ataxic Gait**: Wide-based gait with a tendency to veer towards the side of the lesion.

- **Nystagmus**: Involuntary eye movements may be present.

Cerebellar Vermis Ataxia:

- **Truncal Ataxia**: Difficulty maintaining balance while sitting or standing; often presents with a wide-based stance.

- **Gait Ataxia**: Unsteady, broad-based gait; patients may sway and have difficulty turning.

- **Postural Instability**: Increased risk of falls due to poor balance.

- **Speech Changes**: Dysarthria may occur characterizedd by slurred speech.

- **Nystagmus**: Similar to hemisphere lesions, may also be observed.

General Features Across Types: - Both types can exhibit signs of cerebellar dysfunction such as hypotonia and altered reflexes.

- Exaggerated Reflexes (Hyperref):

- Commonly observed in cases of cerebellar lesions, particularly affecting the hemispheres.

- The cerebellum normally modulates reflex activity; when it is impaired, motor pathways can lack inhibition, leading to exaggerated reflex responses.

- Examples include brisk deep tendon reflexes or clonic responses during testing (e.g., Stewart-Holmes sign).

- Hypotonia in cerebellar pathology manifests as decreased muscle tone; patients may exhibit a "floppy" appearance, with limbs that feel loose and lack resistance to passive movement. This is particularly noticeable in the arms and legs. Pendular reflexes are one of its manifestations.

Clinical examination:

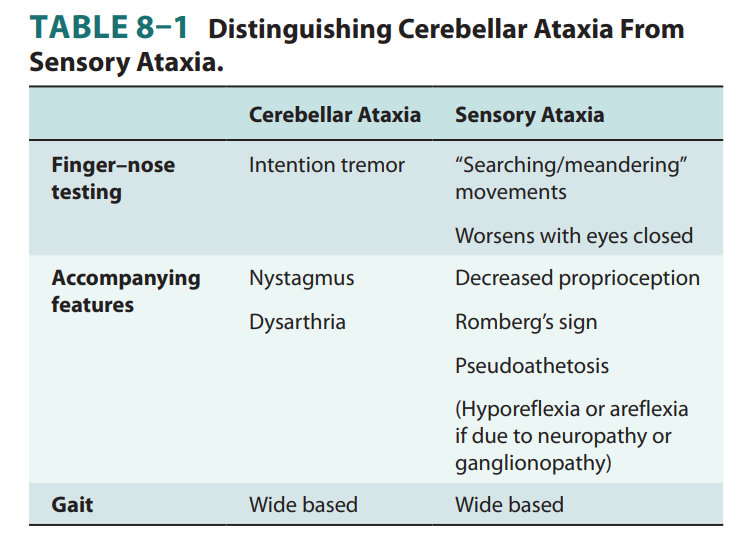

To differentiate the type of ataxia during a clinical examination, focus on specific tests and observations:

Cerebellar Hemisphere Lesions (Peripheral Ataxia):

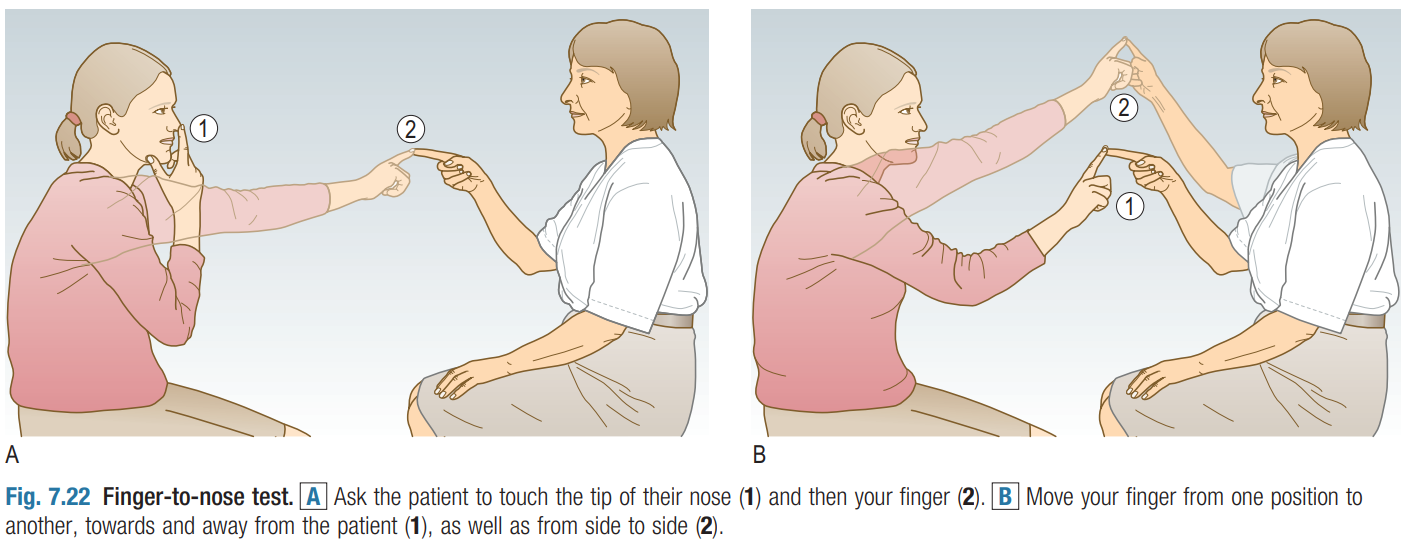

- Perform the **finger-nose test**: Ask the patient to touch their nose and then your finger .Look for dysmetria (overshooting or undershooting).

Finger-to-nose test

Ask the patient to touch their nose with the tip of their index finger and then touch your fingertip. Hold your finger at the extreme of the patient’s reach (you should make the patient use the arm outstretched).

• Ask them to repeat the movement between nose and target finger as quickly as possible.

• Make the test more sensitive by changing the position of your target finger. Timing is crucial; move your finger just as the patient’s finger is about to leave their nose, otherwise you will induce a false-positive finger-to-nose ataxia.

• Some patients are so ataxic that they may injure their eye/ face with this test. If so, use your two hands as the targets or ask the patient to touch their chin rather than nose.

- Assess **rapid alternating movements**: Observe for dysdiadochokinesia, which indicates impaired coordination.

Rapid alternating movements

Demonstrate repeatedly patting the palm of your hand with the palm and then the back of your opposite hand as quickly and regularly as possible. • Ask the patient to copy your actions.

• Repeat with the opposite hand.

• Alternatively, ask the patient to tap a steady rhythm rapidly with one hand on the other hand or table, and ‘listen to the cerebellum’; ataxia makes this task difficult, producing a slower, more irregular rhythm than normal.

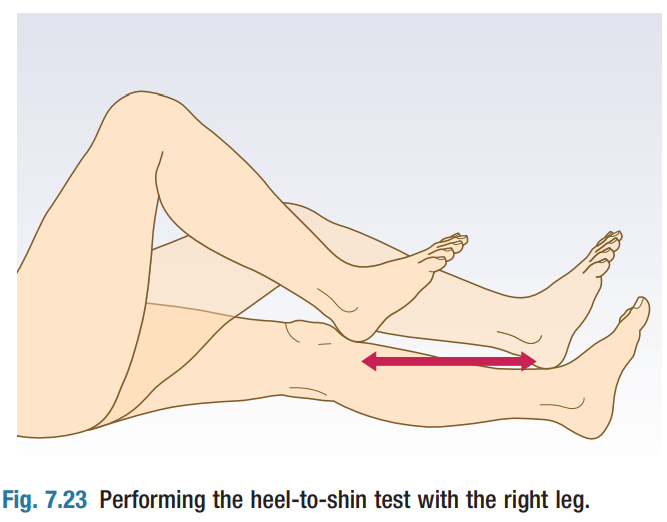

- Evaluate **heel-shin test**: Inability to perform this smoothly suggests cerebellar dysfunction.

Heel-to-shin test

With the patient lying supine, ask them to lift the heel into the air and to place it on their opposite knee, then slide their heel up and down their shin between knee and ankle . The finger-to-nose test may reveal a tendency to fall short of or overshoot the examiner’s finger (dysmetria or past-pointing).

In more severe cases there may be a tremor (or an increase in amplitude of tremor) of the finger as it approaches the target finger and the patient’s nose (intention or hunting tremor).

The movement may be slow, disjointed, and clumsy (dyssynergia).

Dysarthria and nystagmus also occur with cerebellar disease.

Much less reliable signs of the cerebellar disease include the rebound phenomenon (it's the inability to properly regulate muscle contraction following a sudden removal of resistance during a movement),pendular reflexes( reflex response characterized by repeated oscillations or swings of a limb afterstimulus is applied) and hypotonia.

Rebound Phenomenon

Pendular reflexes

Cerebellar Vermis Lesions (Gait Ataxia): - Observe the patient's **gait**: Look for a broad-based stance and unsteady walking, characteristic of truncal ataxia.

- Conduct the **Romberg test**: Have the patient stand with feet together, eyes closed.

63 Y.O male, with diabetes Mellitus; complains of difficulty walking for the past three months on examination, the patient presents with a positive Romberg sign; he loses balance when he closes his eyes

Nystagmus or speech changes, which can provide further clues to the underlying pathology.

- Consider history and other neurological signs to contextualise findings.

This video summarizes the clinical examination.😉

Etiologies :

Hyperacute-onset (over seconds to hours) of cerebellar pathology can be caused by:

• Vascular causes: ischemic stroke, cerebellar hemorrhage

• Toxic: alcohol, cytarabine

Acute-onset (over hours to days) of cerebellar pathology can be caused by:

• Immune-mediated:

• Postinfectious cerebellitis (most commonly seen in children after a viral illness, most commonly varicella infection)

• Flare of multiple sclerosis

Subacute-onset (over weeks to months) of cerebellar pathology can be caused by:

• Infection: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

• Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, which can be associated with anti-Yo (ovarian and breast cancer), anti-Hu (small cell lung cancer), anti-Tr (Hodgkin’s lymphoma), anti-Ma2 (testicular cancer), and anti-GAD (often not associated with a malignancy) antibodies

• Tumor: medulloblastoma (in children), metastatic tumor (in adults)

• Metabolic causes: vitamin E deficiency (acquired or inherited)

Chronic-onset (over years) of cerebellar pathology can be caused by:

• Chronic medication/toxin exposure: phenytoin, alcohol

• Degenerative etiologies

• Acquired: multiple systems atrophy cerebellar type (MSA-C)

• Inherited: Friedreich’s ataxia (autosomal recessive) , Spinocerebellar ataxias (autosomal dominant) ,Fragile X–associated tremor ataxia syndrome (X-linked)

Vascular, infectious, multiple sclerosis lesion–related, and malignant etiologies of cerebellar disease usually lead to unilateral cerebellar dysfunction, whereas drug-related, metabolic, degenerative, and non-multiple sclerosis inflammatory etiologies (e.g., paraneoplastic or postinfectious) more commonly lead to bilateral cerebellar dysfunction.

Investigations:

To diagnose the underlying cause of ataxia, clinicians often rely on:

- Neuroimaging: MRI scans can reveal structural abnormalities in the cerebellum.

- Lumbar Puncture: This may be performed if an inflammatory or infectious process is suspected.

Management Goals:

The primary goals of managing ataxia involve addressing the underlying cause and improving functional abilities. Treatment may include:

- Physical therapy to enhance coordination and balance

- Occupational therapy for assistance with daily activities

- Medications targeting specific conditions contributing to ataxia

Resources

-''macleods_clinical_examination'' -''Clinical Neurology & Neuroanatomy: A Localization-Based Approach, Second Edition''

Member discussion